Taliban 2.0: Vice and Virtue Laws, August 2024

Women must not:

· Be seen

· Be heard

· Be educated

· Go out unescorted

· Have a job

· Look at males to whom they are not related

· Choose not to marry or choose whom they marry.

Punishments: flogging; stoning; rape. And various other forms of legally sanctioned or legally ignored violence.

Taliban 1.0: 1996-2001

Women must not

· Be seen

· Be heard

· Be educated

· Go out unescorted

· Have a job

· Look at males to whom they are not related

· Choose not to marry or choose whom they marry.

Punishments: flogging; stoning; rape. And various other forms of legally sanctioned or legally ignored violence.

SPOT THE DIFFERENCE.

Anecdote. In late March, 2000, I was on a British Airways plane at Islamabad International Airport, Pakistan, waiting for boarding to finish and the plane to take off for Manchester. The atmosphere was tense as our departure coincided with that of then US President Bill Clinton. (As concerns Afghanistan, Clinton expressed more public concern at that time about the Taliban’s destruction of Buddhist statues than he did about their destruction of the lives of Afghan women and girls.)

Also boarding was a rather large extended family-and-friends group, all in black, with the men wearing beards and the women wearing chadors. (Have you ever watched a chador-clad woman trying to eat on a plane? It is very labour-intensive. One hand is occupied with slightly lifting the veil, while the other brings food to the mouth underneath it, being careful not to end up spilling the food as one goes.) As the group was large, and possibly organised its seating a bit late in the day, the group members were spread across various rows. The patriarchs of the group kept moving around the cabin checking on the apparel and behaviour of the group’s female members. They ignored several requests from the flight attendants to sit down as the plane was preparing for takeoff. In the end, one woman flight attendant simply bellowed at them, as might a primary school teacher to a rowdy class: SIT DOWN!!!!

It was funny at the time. We asked her later if it was often like this. She replied in the affirmative with a rueful laugh. She looked a little harried.

Welcome to a Day in the Life. But that was Pakistan. Even in its worst excesses, Pakistan is a picnic in the park (albeit perhaps one taking place during a thunderstorm) compared to what life is like for women in Afghanistan. From the logistics of dealing with going about the day in a Wearable Tent (they are hot—often made of synthetic material, cumbersome, hard to see out of, difficult to do very basic things while wearing, and so on), to the obliteration of one’s personhood behind walls of silence and shame, to the constant threat or reality of physical and sexual violence as punishment for any real or imagined transgression, Afghan women are living in the worst of prisons. On our watch.

“If women really mattered…”

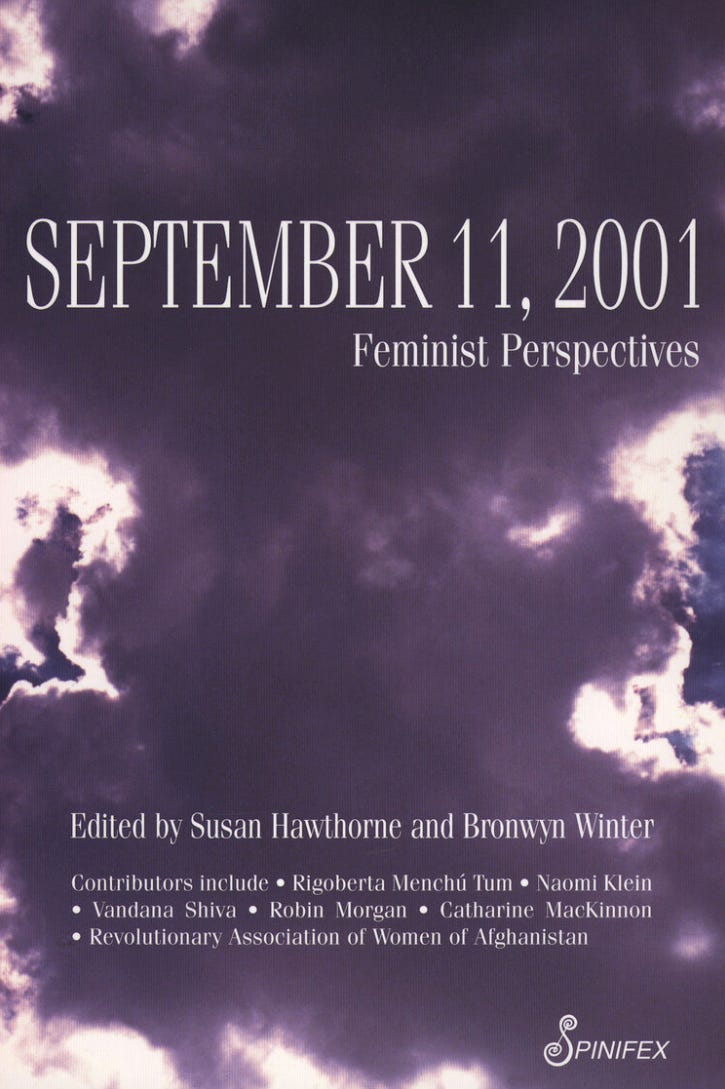

That was the title of my final chapter in the first international feminist anthology on 9/11 and the “War on Terror” (isn’t that just sooo cute when political leaders declare war on concepts?), co-edited by myself and Susan Hawthorne and published by Spinifex Press in 2002, with a North American edition appearing the following year. The chapter documented my short but experientially-crowded visit to Afghanistan in June 2002, as part of a French and United-Statian delegation to the women’s conference immediately preceding the Loya Jirga, which set up the transitional administration of Afghanistan following the 2001-2 war declared by the US. A strong moral justification for that war was “liberating” Afghan women—the same women about whom Clinton had cared so little just a couple of years earlier. I doubt that Bush Jnr cared about them any more. But it read well in the press. And, to my surprise, some Afghan women at the conference were walking up to the US women and saying “thank you.” Thank you for bombing us. Thank you for ending Taliban rule. Now, help us. Please, help us.

In Afghanistan as elsewhere, even the feminist politics were complicated. Our conference was organised by the association Negar, although my personal affinities probably lay somewhat more with RAWA (Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan) and we published statements produced by RAWA in the book. But when one comes from outside the frame, one talks to everyone to try to make sense of what is going on. One talks to all the women who are fighting for women’s lives.

Frankly, dear readers, I could not make much sense at all of what was going on for women. They were fighting so many complicated battles back then:

· the women who had been abducted and raped by the Taliban who now carried the shame of the violence perpetrated against them (we know about that one, don’t we?);

· the women who were trying to look after family members who had been opium farmers and become opium addicts (Afghanistan was then the world’s leading opium supplier and far from stopping the trade, the Taliban profited from it; Myanmar, another country ravaged by militarisation and authoritarian regimes, took over as opium leader in 2023);

· the women who were left as the breadwinners for their families, but could not read nor write and had no “job skills” because they had been forbidden from developing any;

· the women who were, like all women in times of war—and in that “postwar” that can go on for sometimes decades—trying to heal the wounded, the sick, the traumatised, trying to give their children hope; trying to patch the social fabric of their country together.

And in the Loya Jirga warlords and others were jockeying for position but agreeing on the fundamentals: a sharia-based way forward. Women still needed to be controlled, but maybe the iron fist could wear a velvet glove from then on.

Do you know what was getting rebuilt the fastest in post-9/11 Afghanistan? Petrol stations and mosques. At least that was what I saw shooting up all over the landscape while houses, hotels, businesses, streets lay in ruins. My impression may not reflect what was actually happening but it was a striking one, and I was not the only woman in our delegation to have observed it.

Yet, there were significant changes. Another striking memory is of the joy of little girls attending schools in UNHCR tents. They had no writing materials: they learned things by heart. But they smiled. A great deal. Women started attending university, holding down jobs, running for political office. They uncovered their faces if not their heads. They were allowed a little fresh air. There was hope.

Then the US decided it was no longer in its interest to remain in Afghanistan. So it did a deal. With the Taliban, which had already been regrouping for some time as the Western presence slowly diminished. Result: Afghan women have been hurled into a time warp, and not of the Rocky Horror kind. Just the horror kind.

My conclusion in 2002 was that women don’t matter. We matter only when it is in our rulers’ interest to make concessions. Equality between the sexes and “empowerment” of women has often been mobilised in the service of nation-building. It was the case in Third Republic France, it was the case in Kemal Atatürk’s Turkey—two examples that many, including myself, have cited. More often, however, the subjugation of women has been a key instrument in the subjugation of a people.

The questions remain the same: who is harmed, who benefits, and who cares.

Who cares.

It is very very sad. If we weren't having to put our energies into protecting our own rights from the AHRC and our own government, we could be fighting this, and so much more on a global level. But we have to get our own house in order first. It is infuriating.

Thank you Bronwyn. You are right that the ‘men’ don’t care. And they don.’t care because it has nothing to do with them. Just as men don’t care about ‘gender’ because that also has nothing to do with them unless they want to dress,up in fetishistic garments that give them a kick. Sorry I got a bit off topic. I answered a question this week about my idea of hell. I said having to wear a burqa, all day ever day.