The inventor of nursing as a profession (and renowned statistician), Florence Nightingale, was also a prolific writer: of books, pamphlets and articles. In her Notes on Nursing: What It Is, What It is Not can be found these two sentences:

Badly constructed houses do for the healthy what badly constructed hospitals do for the sick. Once insure that the air in a house is stagnant, and sickness is certain to follow.

(It is also suspected that the deeply religious Nightingale may have been a lesbian. She shunned relationships with men and all her close relationships appear to have been with women, although she did not always hold women in general in high esteem. But all this—on the lesbians arguably hidden from history, or arguable lesbians hidden from history, and on women’s often conflicted attitudes towards other women, internalisation of misogyny being what it is—is a topic, or perhaps several topics, for another day.)

In the midst of international and national focus on Israel and Gaza, Ukraine and Russia, Liberal Party election nomination stuff-ups, the new Olympics furore over a male Paralympian turned trans and now competing with women, or whether Ray Gun was good or terrible (in either or both of breaking performance or scholarship1), you may wonder, dear readers, why the hell I am writing today about a topic as unsexy as our health system.

Well, here’s your answer. In its 14 August, 2024 edition, the ABC’s current affairs program The 7.30 Report featured a segment on “the private hospital sector in crisis”. What, them too? I asked, seeing as we’ve been hearing and reading about the crisis in our public hospital system, since, oh, forever. Ambulance ramping times are skyrocketing; workers are quitting the system—especially since the pandemic—such as doctor John Simpson and nurse Amy Halvorsen, who both quit in 2022; the Australian Department of Health has just released a report on the growing national GP shortage; mental health problems among young people, especially women and girls, are on the increase; and so on.

These and many other reports of crises in Australia’s health system over recent years suggest that, figuratively, we are indeed living in badly constructed houses and being cared for in badly constructed hospitals. Especially if completely reliant on the public system: the single biggest determinant of health outcomes is—you guessed it—socioeconomic. The poorer you are, the sicker you are likely to become.

But to return for a moment to The 7.30 Report segment. The segment featured a heterosexual couple in a private hospital in a non-urban region of Australia who were “having a baby”. Say what? Er, isn’t it women who have babies? You know, those birthing people, those cervix havers, the people that anyone with a reasonable grasp on reality understands to be women (i.e. female people) and mothers. Dad may be a co-progenitor of the neonate, and a contributor to its raising, but he didn’t actually have the baby. This is yet another example of the semantic slippage in our institutions and media that disappears women: in this case it is mothers who are disappeared in the warmandfuzzy inclusion of Daddy in the process of giving birth. Well, at least Mummy wasn’t referred to as a birthing person. For that, I suppose, we should be grateful.

That was the first thing that made me sit up and take notice. The other one, and the focus of today’s post, was that the private hospital system that is supposed to fill the gaps in the public one (assuming you have the means to pay for it)—especially, it seems, in rural areas, is now also floundering. Say what? A $22 billion industry floundering? Since when did we simply take it for granted that the private health sector is part of the essential health service provision in this country, and since when are we supposed to be contributing (even) more to private health funds to shore it up? I can understand United Statians thinking that way, because public health coverage is so abysmal (albeit somewhat improved since the 2010 passage of the Affordable Care Act) and so expensive, that private is the name of the health game there. (Even so, the US actually spends more than any other OECD country on health as a proportion of GDP. Go figure.)

But in Australia? Medicare (then Medibank) was introduced in 1975 by the then Whitlam government (Labor). It would have happened during that government’s first term from 1972 had the federal opposition, then led by Malcolm Fraser (Liberal), not consistently rejected bills relating to its financing. Once in power, the Fraser government did its darndest to undermine it and preserving Medibank was the focus of one of the last truly political strikes in Australia, by 2.5 million people in 1976. Ah, them wuz the days. Yes, younger readers, people used to go on strike to defend the public good, not just within the framework of Enterprise Bargaining. Unfortunately, that strike only served to delay the ultimate outcome: in 1981 the Fraser government entirely dissolved Medibank as a public health system, leaving only the then not-for-profit Medibank Private insurance fund as a government-run fund. The Hawke government reinstated the public system under the name Medicare in 1984 and Medicare remains with us to this day.

The point of this little excursion into history is that all but the very oldest among us grew up taking some degree of public health coverage for granted (except dental care which is one major lacuna in our public health system). They further took for granted that if they wanted to go private, they had an extra government-run, not-for-profit Medibank fund at their service as well.

That all changed in 2009 when the Rudd government (Labor) changed Medibank Private to a for-profit fund, and more drastically in 2014 when the Abbott government (Liberal-National) privatised it altogether. It is now listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. There were earlier shifts too. In 1997, the Howard government brought in a Medicare surcharge to push people earning higher incomes into taking out private health insurance in order to shift resources to the private system. The bulk of the private health insurance market is now held by only two commercial firms: Medibank and BUPA, which between them corner over 52% of the private health insurance market. Mutualist funds (associated with trade unions among others), are a tiny share of the private health insurance market.

Today, roughly half of all Australians have private health insurance for various ancillary medical (dental, physiotherapy and so on) and hospital extras cover.

Yet, OECD statistics show that government health spending in member states as a proportion of GDP or per capita of population has for the most part steadily increased since the beginning of this century, notwithstanding a post-pandemic dip. Australia is either on a par with the OECD average or slightly better than it, but it is nonetheless outdone by many comparator countries in Europe and North America, some of which, like the USA as mentioned above, are hardly shining examples of egalitarianism in healthcare.

There are many reasons for the increase in government spending, one of which is an ageing population, but another major factor is costs of medical interventions and a rise in the incidence of chronic diseases, this last being linked to what is often euphemistically called “lifestyle”. But the sense of crisis is undeniable: shortage of qualified practitioners in areas where they are needed; overworked, overstressed and underpaid health professionals leaving the sector; and differences in access to healthcare.

Which leads us back to that 7.30 Report segment. One of the many crises affecting our health system is the lack of access to healthcare in outer regional and remote areas. According to David Butt of the National Rural Health Alliance, writing in 2017, the then 1.3 million people living in those areas and paying for private health insurance were not getting bang for their buck, or medicine for their moolah if you will. Butt concluded that their contributions were helping to keep private health insurance costs down but the main beneficiaries were those in inner regional and urban areas. Another 1.5 million then living in those areas just “didn’t bother” with private health insurance. The 7.30 Report segment documented increased costs faced by private providers, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic (which seems to have provided an excuse for companies in all sectors to operate a price hike, as we know from our increased rent, food and utilities bills).

More recently, in April 2024, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare documented the greater health problems and needs experienced by the roughly 10% of Australians living in outer regional and remote areas. While health problems were greater among men, women were more at risk on another level: women living outside major cities are 1.5 times more likely to have experienced partner violence than women in cities. This is a regional-and-remote health and welfare problem that should surely be a top priority: Greens Senator Dorinda Cox certainly thinks so. On the day I am writing these words, Cox has condemned the just-released government report on murdered Indigenous women as “toothless”. Indigenous women are three times more likely to experience partner violence than non-Indigenous women. They are also three times more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to live in outer regional and remote areas (even though the majority of Indigenous people, contrary to the assumptions of many, live in urban and inner regional areas, mostly in NSW and Qld).

There are some 650 private hospitals in Australia, compared to 697 public ones in 2021-22, although the actual number of hospital beds is—understandably given the demand—double in the public sector. In June this year federal Health Minister Mark Butler announced an “urgent” review into the private hospital system, “as it faces intense financial stress driven by rising labour and input costs and constrained revenue” (Australian Financial Review, 12 June). The findings are due sometime between now and the end of August. Let’s all hold our breath.

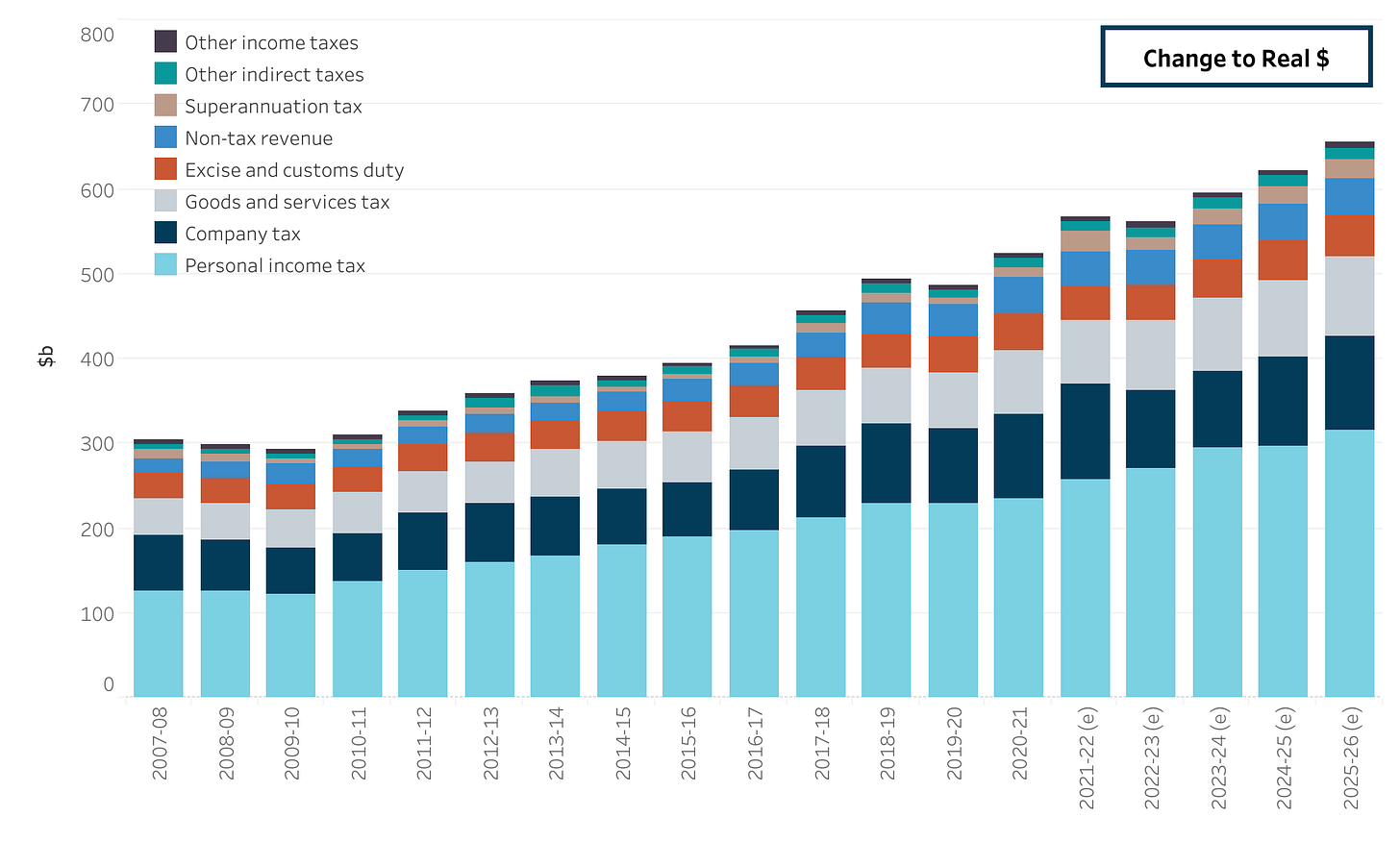

Meanwhile, the question remains: if health is the second-largest expenditure item in federal spending (see table below, shown in nominal dollars, that is, not adjusted for inflation), then why are we soooo dependent on the private sector to “fix” outer-regional-and-remote healthcare problems, while the public hospital sector languishes in a mess of overcrowding, underresourcing and staff and patient stress?

When did we stop thinking of high-level healthcare as a public and common good to which all people have a fundamental right in this country? When did we start to expect the for-profit sector to fill the gaps in fundamental services that those outside urban and inner regional areas experience? When did we start to think of health as something that the better-off are entitled to while the poorer just muddle along? Did we always think of it that way? Surely not.

I will leave you today, dear readers, with two more unsexy facts, the first related to the health workforce and the second related to… well, you’ll see.

First, while the private health sector is complaining about rising labour costs, let us remember that three-quarters of the health workforce in all areas is female, and women are concentrated in the less-well-paid and lower-status areas such as nursing and midwifery (88% of all of these are female, and they are paid, on average, between one quarter and one third of what hospital emergency physicians are paid). The exception here is dentistry, where women slightly outnumber men. Even here, though, female dental specialists (the really high earning lot) are less than 30% of the total in that area.

So when health providers are talking about rising labour costs, who exactly is being perceived as the most costly?

Second, although according to the ATO companies are paying more tax these days, 800 large companies still paid zero tax in Australia in the 2021-22 financial year. We probably always had an inkling that tax law favours corporations, but the graph below shows just how little government revenue comes from company tax, compared to personal income tax (that’s you and me, readers) and roughly on a par with goods and services tax (also you and me because we’re the ones paying it). Now, let us sit and ponder what the government could do with that money if these corporations coughed up.

I highly recommend Szego Unplugged on this last; also on the first for that matter.